6 January 2025

Author: Ishika Joshi, Policy Researcher, QETCI

Quantum technology has moved from research labs to a strategic priority within national strategy, shaping how countries define economic competitiveness and technological sovereignty. Across the Asia–Pacific (APAC), collaboration in quantum technology remains nascent and uneven, despite expanding national investments and mission-level aspirations. The Quad Investors Network (QUIN) is one such key example of this evolving dynamic.

Governments in the region have poured resources into national quantum programs, but most initiatives continue to advance domestically. Even where countries have signed MOUs or launched limited joint projects, the activity remains narrow and does not yet resemble the kind of structured, multi-country cooperation needed to support shared infrastructure, interoperable standards or integrated talent pathways.[25,pp.5,9,10,11,19,24,42,47; 35,36]

Strategic caution around quantum technologies tied to cybersecurity, defence, and secure communications keeps governments protective of assets and data. As a result, APAC’s progress remains largely shaped by national priorities, with regional coordination still evolving.

The Global Contrast

In contrast, other regions are building structured and long-term quantum alliances that embed cooperation into governance. The United States and United Kingdom formalized their partnership through the Technology Prosperity Deal, covering joint work on quantum sensing, algorithms, and workforce mobility. This deal is backed by coordinated funding calls between the US-NSF and UKRI and a dedicated Quantum Industry Exchange Program, creating a sustainable bridge between research and commercialization. [1] This example illustrates a fully integrated collaboration model, one where policy, funding, mobility, and industry linkages operate as a single framework.

The European Union takes an even more systemic approach. The European Quantum Flagship and EuroQCI initiatives link over 20 nations through shared research infrastructure, open funding frameworks, and interoperability standards. The EU plans to institutionalize through the upcoming EU Quantum Act.[50] Beyond collaborating through EU frameworks, European countries, Germany and France for instance, run cross-border quantum projects as well. [2-4]

The region does participate in several international partnerships, but these tend to be focused on specific themes or bilateral exchanges rather than anchored in a shared, long-term regional structure.While APAC countries do engage in bilateral, multilateral, and thematic partnerships, but such a consolidated structure for collaboration is still uncommon across the region.

These examples show a clear contrast: while international ecosystems align around common governance, standards, and mobility; APAC region remains a collection of parallel programs, each strong individually but disconnected collectively.

The Regional Story

China

China’s collaborations remain limited and selective, with partnerships including Austria, Spain, Russia, South Africa (quantum communication link), and Pakistan (quantum technology MoU). Its quantum satellite experiments done in collaboration with the University of Vienna demonstrated the maturity of China’s quantum communication infrastructure through the Micius satellite, which provided the essential technology needed to bridge long distances for secure key distribution in quantum communication. The country continues to focus primarily on self-reliance while selectively engaging international partners for strategic cooperation and joint research initiatives. [6.pp,8,9;7.pp,1,3;21-23;37;38]

Singapore

Through its National Quantum Office (NQO) and Centre for Quantum Technologies (CQT), Singapore has built one of the most extensive quantum collaboration networks in the region. With formal partnerships spanning CNRS (France), and institutions across Japan, Netherlands, and South Korea, and industry leaders like IBM and Quantinuum to drive joint research, applications, and talent development in quantum technologies. Singapore functions as a regional hub facilitating shared testbeds, staff exchanges, and infrastructure access. Its strategy emphasizes connectivity and collaboration, positioning the country as an anchor for quantum experimentation and commercialization in Asia.[8;9.pp,1,4;19.p,1]

India

India’s National Quantum Mission (NQM) operates through a hub-spoke-spike model, anchoring its efforts to enable distributed development across core domains. Internationally, India follows a goal-oriented approach to collaboration, engaging in focused partnerships that align with its mission priorities. Most visible are its research and capacity-building links with Singapore, Japan, and the United States, including testbeds, joint workshops, and academic exchanges. Key partnerships include the U.S.–India iCET (Initiative on Critical and Emerging Technology). and Quantum Coordination Mechanism, the UK–India TSI (Technology Security Initiative), and the Australia–India AICCTP (Australia-India Cyber and Critical Technology Partnership), complemented by cooperation through the Quad QUIN QCoE (Quantum Centre of Excellence). India has also signed quantum MoUs with Canada, France, Israel, Finland, Japan, and Italy[10;11;20.pp,35;42,43]

Japan

Japan advances quantum development through structured, alliance based partnerships. The Tokyo Statement on Quantum Cooperation with the United States set the foundation for joint work in computing, communication, and sensing, emphasizing shared values and research security. Under the EU–Japan Digital Partnership the Q-NEKO project unites 16 partners to develop hybrid quantum classical systems for materials, biomedical, and climate applications reflecting Japan’s focus on capability building through interoperability and trusted alliances. Japan also maintains regional collaborations and industry partnerships, with initiatives such as Australia–Japan quantum dialogues and the Quantum Development Group serving as examples. [12,13,33,34]

Australia

Australia advances quantum research through trusted partnerships that blend security priorities with open collaboration. The AUKUS Quantum Arrangement (AQuA) anchors collaboration on secure communication standards, workforce mobility, and next-generation defence applications, with an initial focus on quantum positioning, navigation, and timing (PNT) and the integration of emerging quantum technologies through joint trials and experimentation over the next three years. Australia also pursues trusted partnerships with Japan, India, Singapore, the European Union, ASEAN, North America, and the United Kingdom to strengthen research cooperation, establish quantum standards, and strengthen supply chains. Participation in global platforms such as the IBM Quantum Network further strengthens its role as a reliable and connected contributor to the international quantum ecosystem. [14,15,24]

South Korea

South Korea’s quantum efforts are driven by strong industry participation and global partnerships. Collaborations such as the BTQ Technologies (Canada) initiative on quantum-safe communication networks highlight its focus on commercialisation. Alongside domestic programs led by the Korea Research Institute of Standards and Science (KRISS) and alliances with the US and EU on quantum communication and standards, South Korea’s approach emphasises practical deployment, industrial scalability, and international market alignment. [16,17]

ASEAN

Thailand, Malaysia, and Indonesia have joined the global ecosystem through commercial and vendor-driven partnerships. Malaysia’s MIMOS (Malaysian Institute of Microelectronic Systems Berhad) has signed a teaming agreement with SDT (Sigma Delta Technologies Inc., South Korea) to establish the Quantum Intelligence Centre, core of Malaysia’s quantum R&D and a cornerstone of the Malaysia Quantum Valley vision. These partnerships offer training, access to cloud-based quantum systems, and early participation in applied research, pragmatic entry points that bypass the need for large domestic infrastructure. Alongside these national efforts, ASEAN is also building regional quantum collaboration through initiatives such as the ASEAN Committee on Science, Technology and Innovation (COSTI) agenda under APASTI (ASEAN Plan of Action on Science, Technology and Innovation), the ASEAN World Quantum Day programmes, and Singapore-led regional projects including the National Quantum-Safe Network Plus, which support shared standards, capacity building, and ecosystem development across Southeast Asia. These regional efforts have expanded further with the emergence of the Southeast Asia Quantum Industry Association (SEAQIA), which brings together private-sector and research actors across the region to coordinate infrastructure access, promote responsible deployment, and accelerate workforce development. Countries like Malaysia are also building community-led platforms such as MyQI (Malaysia Quantum Information Initiative), which serve as national entry points into ASEAN-level collaboration, while events such as the SEA Quantathon and the upcoming ASEAN Quantum Summit signal a shift toward structured, multi-country engagement and strategic prioritization of quantum technologies within the region. [18;,27.pp,24,65,67;28-31;39,40]

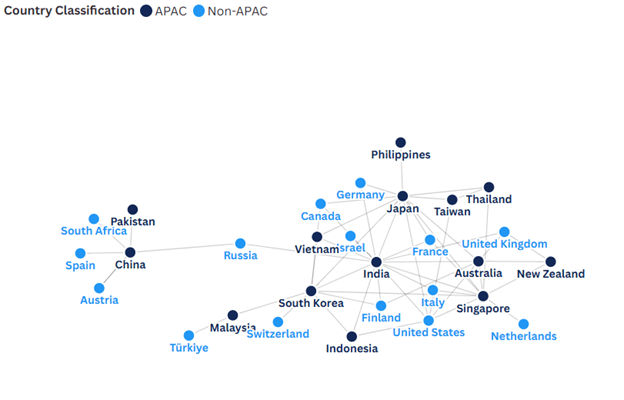

Figure 1: Collaborations in Quantum Technology

Taken together, these efforts point to a scattered but growing pattern of collaboration across the region shaped more by bilateral projects, partnerships, and research exchanges than by cohesive regional frameworks. Each economy pursues its own trajectory, creating a network of initiatives that is active yet uneven in coordination, scale, and strategic continuity.

From Funding to Frameworks: Why Integration Remains Limited

Despite growing activity, structured regional collaboration faces three persistent barriers, each political rather than technical.

Regional Quantum Governance

Regional quantum governance remains cautious, shaped by differing national priorities and concerns over safeguarding sensitive technologies and research. Rather than creating new institutions, progress is emerging through existing platforms, ASEAN science dialogues, QUAD, and global forums such as the Open Quantum Institute and OECD quantum policy networks offering practical avenues for policy alignment, standards, and interoperability. Countries are effectively shopping for forums, choosing platforms that match their capacity and strategic priorities; those with growing capabilities should begin engaging more deliberately with these mechanisms. [25.pp,5,7;26;27.p,107]

Joint Industry–Academia R&D Mechanisms

Cross-border quantum R&D faces challenges rooted in the differing priorities of industry and academia. Industry partners prioritize commercialization, IP protection, and market outcomes, while academic institutions focus on open research and capability building. These misaligned incentives often create value imbalances and strategic friction in multi-country partnerships. A practical path forward is project-based consortia built around shared hubs or testbeds, policy sandboxes for shared standardization and testing, enabling focused collaboration while allowing each country and partner to maintain autonomy over results, intellectual assets, and strategic interests.

Talent Circulation and Workforce Retention

The quantum talent gap is widening globally. The US and EU are increasingly attracting researchers from APAC, leaving domestic programs under pressure. Structured regional fellowship and exchange programs, for example, under ASEAN or QUAD-led science initiatives, could enable controlled researcher mobility while protecting national interests. Quantum Entanglement Exchange Programme, exemplifies this approach, facilitating international researcher exchanges and collaborative capacity building. This issue is becoming critical, as workforce shortages now outpace infrastructure gaps.[25.p,6;27.p,57;35;36]

Why Regional Collaboration Matters

Beyond addressing technical barriers, structured quantum collaboration in APAC carries strategic imperatives that extend well beyond technology itself. International scientific cooperation serves as one of the few practical mechanisms for lowering geopolitical tensions because science operates on neutral, evidence driven principles that transcend borders and politics. [41, 42] Historical precedents demonstrate this resilience: CERN’s post-war integration model, SESAME’s Middle East cooperation platform, Cold War space joint missions, and sustained US–China research during COVID-19 all show that scientific partnerships can survive political hostility or even outlast it. [43, 45, 46, 47] This neutrality creates a substitute diplomatic channel, what some call “ersatz diplomacy”, that keeps dialogue alive when official political channels stall. [45, 46] Scientists routinely collaborate across ideological divides because advancing knowledge outweighs political loyalty, a core principle of scientific globalism. [46] With existential global threats like climate change, pandemics, and environmental degradation forcing collective action, scientific cooperation becomes a diplomatic necessity rather than a luxury. [46, 47] When political systems are gridlocked, Track II scientific networks maintain trust, transparency, and communication, roles that become essential when formal diplomacy falters. [47] In short, science diplomacy offers a rare pressure resistant bridge it builds trust, de-escalates conflict, and sustains dialogue when every other channel breaks down. [41, 43, 47]

For APAC specifically, South-South cooperation among regional nations offers distinct strategic advantages rooted in shared developmental contexts and reduced transactional barriers. Collaboration among developing countries proves mutually beneficial through exchanges of knowledge, skills, and technical know-how that strengthen collective self-reliance via pooled resources and complementary capabilities. The expertise emerging from developing nations evolves within environments of similar factor endowments and relatively poorer infrastructure, making these capabilities more attuned to comparable geo-climatic conditions and inherently more cost-effective when transferred across similar contexts. Such cooperation carries little macroeconomic or governance conditionalities, remaining voluntary, driven by participating countries’ priorities, and fundamentally free from external conditions. This stands in sharp contrast to collaborations with large entities like the European Union, where non-member countries face complex frameworks of numerous requirements and challenges when navigating established programme structures. For APAC nations still building institutional capacity, horizontal cooperation circumvents these burdensome conditionalities while accelerating development through solidarity-based partnerships that respect sovereignty and align with regional priorities.[45,48,49.pp,12-17,21,24]

The Takeaway: Collaboration as Strategy

Quantum leadership will be defined by connectivity, not just capacity. The regions that translate research cooperation into aligned governance, interoperable standards, and shared infrastructure are advancing faster toward real-world deployment.

For the Asia–Pacific, collaboration is not optional, it is the foundation of scale, resilience, and competitiveness. The region’s progress will depend on whether fragmented partnerships can evolve into durable frameworks that balance openness with security and trust.

The next phase of quantum development demands more than ambition or funding. It requires intentional interdependence collaboration built on aligned interests, transparent standards, and shared capability-building. Progress will depend on how effectively the region can move from parallel efforts to coordinated action because, in quantum, isolation slows innovation, but structured collaboration sustains it.

References

- White House. (2025, September 18). Memorandum of Understanding between the Government of the United States of America and the Government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland regarding the Technology Prosperity Deal. https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/09/memorandum-of-understanding-between-the-government-of-the-united-states-of-america-and-the-government-of-the-united-kingdom-of-great-britain-and-northern-ireland-regarding-the-technology-prosperity-de/

- European Commission. (n.d.). Quantum | Shaping Europe’s digital future. European Union. https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/quantum

- European Commission. (n.d.). European Quantum Communication Infrastructure – EuroQCI. European Union. https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/european-quantum-communication-infrastructure-euroqci

- Quantum Computing Report. (2025, September 18). US and UK sign technology pact to advance quantum technologies, establish collaboration framework. https://quantumcomputingreport.com/us-and-uk-sign-technology-pact-to-advance-quantum-technologies-establish-collaboration-framework/

- Guinea, O., Pandya, D., du Roy, O., & Dugo, A. (2025, January). Quantum technology: A policy primer for EU policymakers. European Centre for International Political Economy (ECIPE). https://ecipe.org/publications/quantum-technology-eu-policy-primer/

- MERICS. (2024, December).China’s Long view on Quantum Tech has the US and EU playing catchup. China Tech Observatory: Quantum Report 2024. Mercator Institute for China Studies, https://merics.org/sites/default/files/2024-12/MERICS%20China%20Tech%20Observatory%20Quantum%20Report%202024.pdf

- Omaar, H., & Makaryan, M. (2024, September). How innovative is China in quantum? Information Technology and Innovation Foundation. https://www2.itif.org/2024-chinese-quantum-innovation.pdf

- Centre for Quantum Technologies.(2025) International collaborations. Centre for Quantum Technologies. https://www.cqt.sg/international-collaborations/

- Netherlands Enterprise Agency . (n.d.). Singapore’s strives to become (South East) Asia’s Quantum hub. https://www.rvo.nl/sites/default/files/2025-06/IAN_Singapore%E2%80%99s%20strives%20to%20become%20Asia%E2%80%99s%20Quantum%20Hub.pdf

- Department of Science & Technology. (n.d.). Cabinet approves National Quantum Mission. Department of Science & Technology, Government of India. https://dst.gov.in/national-quantum-mission-nqm

- The Quantum Insider. (2025, February 14). The state of US quantum in flux as partnerships with India and Japan reaffirmed amid research cuts and proposed funding. https://thequantuminsider.com/2025/02/14/the-state-of-us-quantum-in-flux-as-partnerships-with-india-and-japan-reaffirmed-amid-research-cuts-and-proposed-funding/

- European Commission. (2025, May 12). EU and Japan strengthen Research and Innovation cooperation in quantum science and technology. https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/news/eu-and-japan-strengthen-research-and-innovation-cooperation-quantum-science-and-technology

- U.S. Department of State. (2019, December 19). Tokyo Statement on Quantum Cooperation. https://2021-2025.state.gov/tokyo-statement-on-quantum-cooperation/

- Prime Minister’s Office. FACT SHEET: Implementation of the Australia – United Kingdom – United States Partnership AUKUS factsheet. https://pmtranscripts.pmc.gov.au/sites/default/files/AUKUS-factsheet.pdf

- IBM. (2017, December 14). University of Melbourne joins as founding member of IBM Q Network Hub to accelerate quantum computing. https://au.newsroom.ibm.com/2017-12-14-University-of-Melbourne-joins-as-founding-member-of-IBM-Q-Network-Hub-to-Accelerate-Quantum-Computing

- Cierra Choucair (2024, December 31). BTQ Technologies announces collaboration with South Korea’s Future Quantum Convergence Forum and QuINSA. The Quantum Insider. https://thequantuminsider.com/2024/12/31/btq-technologies-announces-collaboration-with-south-koreas-future-quantum-convergence-forum-and-quinsa/

- Marin . (2025, March 14). Quantum technologies and quantum computing in South Korea. PostQuantum. https://postquantum.com/quantum-computing/quantum-south-korea/

- Matt Swayne. (2024, November 26). SDT and MIMOS sign MOU to propel Malaysia’s ‘Quantum Valley’ vision. The Quantum Insider. https://thequantuminsider.com/2024/11/26/sdt-and-mimos-sign-mou-to-propel-malaysias-quantum-valley-vision/

- National Quantum Office. (n.d.). National Quantum Strategy: Media factsheet. National Quantum Office. https://nqo.sg/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/Media-Factsheet_NQO_National-Quantum-Strategy_27-May-clean-1.pdf

- Quantum Ecosystems Technology Council of India & Embassy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. (2025). Unveiling the Indo-Dutch Quantum Frontier – In Search of Opportunities to Integrate Ecosystems. https://qetci.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/QETCI-Unveiling-the-Indo-Dutch-Quantum-Frontier.pdf

- Swayne, M. (2025, May 9). Report: China and Russia test quantum communication link. The Quantum Insider. https://thequantuminsider.com/2024/01/02/report-china-and-russia-test-quantum-communication-link/

- Swayne, M. (2025, October 27). Pakistan, China to deepen quantum technology collaboration. The Quantum Insider. https://thequantuminsider.com/2025/10/27/pakistan-china-to-deepen-quantum-technology-collaboration/

- Swayne, M. (2025, March 14). China establishes quantum-secure communication links with South Africa. The Quantum Insider. https://thequantuminsider.com/2025/03/14/china-established-quantum-secure-communication-links-with-south-africa/

- Australian Government Department of Industry, Science and Resources. (n.d.). National Quantum Strategy: A national and international approach. https://www.industry.gov.au/publications/national-quantum-strategy/national-and-international-approach

- Office of the Principal Scientific Adviser to the Government of India. (2024). Quantum Technologies: Establishing Centres of Excellence (Quantum CoE Report). Government of India. https://psa.gov.in/CMS/web/sites/default/files/psa_custom_files/QUIN_Quantum_CoE_Report_Final.pdf

- CERN. (2024). The Open Quantum Institute (OQI). https://open-quantum-institute.cern/

- Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). (2025). ASEAN Plan of Action on Science, Technology and Innovation (APASTI) 2026–2035. https://asean.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/ASEAN_APASTI_F06_PDF_Singles.pdf

- PostQuantum.(2024, December 27). Quantum technology initiatives in Singapore and ASEAN. PostQuantum. https://postquantum.com/quantum-computing/quantum-singapore-asean/

- World Quantum Day. (2025, June 18). The Southeast Asia World Quantum Day initiatives. World Quantum Day. https://worldquantumday.org/news/the-southeast-asia-world-quantum-day-initiatives

- Quantum Association Asia.(n.d.) Quantum Association Asia. https://www.quantumassociation.asia/

- Infocomm Media Development Authority (IMDA).(n.d.) National Quantum Safe Network Plus. IMDA Singapore. https://www.imda.gov.sg/about-imda/emerging-technologies-and-research/national-quantum-safe-network-plus

- Gesda Global.(n.d.) Open Quantum Institute. https://www.gesda.global/open-quantum-institute/

- Australia Embassy Tokyo. (2025, May 14). Remarks at the Australia-Japan Quantum Technology Collaboration Summit. Australian Embassy Tokyo. https://japan.embassy.gov.au/tkyo/HOM_Remarks_quantum.html

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan. “The Forth Meeting of the Quantum Development Group.” Press Releases, 9 September 2025. https://www.mofa.go.jp/press/release/pressite_000001_01642.html.

- Japan Science and Technology Agency. (2025, January 23). Quantum technology trends in Asia-Pacific: Insights from Japan Science and Technology Agency. https://sj.jst.go.jp/news/202501/n0123-01cac.html

- Kacki M. .(n.d.) The geoeconomics of quantum technology in the Indo-Pacific. Perth USAsia Centre. https://perthusasia.edu.au/research-and-insights/the-geoeconomics-of-quantum-technology-in-the-indo-pacific/

- MERICS. (2025, October 2). China starts exporting quantum computers as its systems become more competitive. MERICS. https://merics.org/en/comment/china-starts-exporting-quantum-computers-its-systems-become-more-competitive

- Austrian Academy of Sciences. (2018, January 19)Secure quantum communication over 7,600 kilometers. ÖAW. https://www.oeaw.ac.at/en/news-1/secure-quantum-communication-over-7600-kilometers-2

- International Year of Quantum Science And Technology. (n.d.). ASEAN Quantum Summit. https://quantum2025.org/iyq-event/asean-quantum-summit/

- MyQI. (n.d.). MyQI. https://www.myqi.my/

- International Science Council. (2023, May 26). Mitigating crisis: The power of science diplomacy. https://council.science/blog/mitigating-crisis-the-power-of-science-diplomacy/

- Benmouna, M. (2023, October 10). Nurturing peace through science diplomacy. The World Academy of Sciences (TWAS). https://twas.org/article/nurturing-peace-through-science-diplomacy

- Mouslim H. (2025 , August 30). The Quiet Diplomats: How Science Is Building Bridges in a Broken World. International Journal of Research and Innovation in Social Science (IJRISS), 9(08), 1318-1328. https://doi.org/https://dx.doi.org/10.47772/IJRISS.2025.908000110

- Van Langenhove, L., & Piaget, E. (2024, July 19). Leveraging science diplomacy in times of conflict. Georgetown Journal of International Affairs. https://gjia.georgetown.edu/2024/07/19/leveraging-science-diplomacy-in-times-of-conflict/

- Tim Flink, (2022, April 2) Taking the pulse of science diplomacy and developing practices of valuation, Science and Public Policy, Volume 49, Issue 2, April 2022, Pages 191–200, https://doi.org/10.1093/scipol/scab074

- Shih, T., Chubb, A. & Cooney-O’Donoghue, D. Scientific collaboration amid geopolitical tensions: a comparison of Sweden and Australia. High Educ 87, 1339–1356 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-023-01066-0

- luckman, P. D. (2022). Scientists and scientific organizations need to play a greater role in science diplomacy. PLoS Biology, 20(11), e3001848. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9624423/

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. (n.d.). Statement on South-South Cooperation and Capacity Development. United Nations. https://www.un.org/en/desa/statement-south-south-cooperation-and-capacity-development

- Mitka, M., & Dohain-Lesueur, R. (2025). Voices from the Horizon: Third Countries’ Experiences Guiding the Design of FP10. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14794907

- Moody’s, “EU to propose Quantum Act to govern and scale quantum capabilities”, 31 October 2025, https://www.moodys.com/web/en/us/insights/regulatory-news/eu-to-propose-quantum-act-to-govern-and-scale-quantum-capabiliti.html. Accessed on 27 November 2025.